Jenkin

JENKIN LLOYD JONES

November 14, 1843 - September 12, 1918

My great grandfather, the Reverend Jenkin Lloyd Jones, looms large in the minds and lives of his descendants.

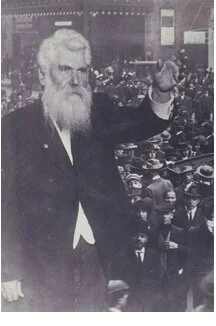

Pictures are plentiful—the young, high-cheeked, closely-shaven private of the American Civil War (the only time we see him without a beard); the prophet-like preacher at the pulpit, gesturing widely; the vigorous observer of humanity, seated on his favorite horse and wandering the land he had come to love; the serene family man side by side with Susan, his wife and helpmeet of many years, his brash, bright young son, Richard, and sweet daughter, Mary.

More to the point, the huge impact Jenkin Lloyd Jones made on his contemporaries in terms of high-thinking, erudition, morality, mental challenge—coupled with his call to arms to be of USE to one’s fellow man—has filtered down through the generations. His son Richard used a newspaper as his pulpit, as did his sons, and his sons’ sons after him. The newspaper Richard founded, the Tulsa Tribune, would have pleased Richard’s father. For the sixty years that it lived, it was a crusading paper, vigilant against graft and corruption, fighting for good, and hugely respected among its peers. A bully pulpit.

Meanwhile, the Grand Old Man’s own works continue to this day in the Abraham Lincoln Center in Chicago that he founded in 1905. The Center has metamorphosed into a series of outreach facilities—Job Training, Head Start, After School gatherings, Mental Health—the vision goes on and on through more than a hundred years of service to mankind.

Jenkin was the Lloyd Jones who slipped the yoke of the farm . . . the one who followed a far-reaching vision . . . the one with world-impact. As one looks at the Uncles in their Valley and the Aunts with their broods of children, one wonders about their visions—for they had them—and their potential—for it was considerable—had they been given a comparable chance. But it was Jenkin’s lot to be the one to roam—and to bring both honor and calumny to his life.

Family lore abounds about Jenkin, last of Richard and Mallie’s Welsh-born brood.

He was only a year old when the family made its hazardous crossing to the New World. That siren call of freedom, land, and opportunity had worked its will on Richard and Mallie, and they dared much to leave the familiar and come to the unknown. That same daring and trust in God and the future molded their children and indelibly stamped the family “the God-Almighty Joneses.”

From the distance of a century and a half, we catch snatches of their seventh-born child, Jenkin—his upbringing and impact:

The immigrant boy, too young to help build corduroy roads and wrestle a living from stony ground and sunless Wisconsin forests, but already astute enough to observe and absorb the unflagging efforts of his elders.

The wide-eyed observer whose strong-willed parents were adjudged “heretics” by the very men they hosted in their simple Wisconsin cabin. In later years Jenkin would refer to that episode as “Black Week.” His parents’ crime: to join the local church while adhering to their private faith. The “trial” ended only when they withdrew from the church to protect its pastor from condemnation, but the trial’s impact remained in the child’s mind, forging an adult’s steel backbone against strict, unyielding, intolerant orthodoxy.

The child farmer, taught to work the land as his parents and siblings worked the land, surrounded by haphazard dangers, unpredictable weather, ever-present need . . . and boundless optimism.

The youthful soldier in a war between sister states that wrenched him from all that was familiar and sent him South as a lowly private (1862-65). The farming pattern was broken. The world expanded. There, in a Cause he upheld with whole heart, he learned the dark side of war. “Oh what a wrong way to do a right thing!” It was a lesson he was to preach to the end of his days.

For that is what he became. A preacher. One more of a long line of free thinkers and high-minded heretics stretching back generations and reaching forward with thunderous voice into the future. Would he have preached without the war to goad him? God knows. But his heritage and yearnings met and melded in the war and he never quite fit on the family farm again.

Meadville, Pennsylvania became his destination and destiny (1866-1870). There, at the Meadville Seminary, he rose at four in the morning to do odd jobs between studies in order to pay his way. That way was long—a full year longer than other students—as his instructors strove to knock the harsh, untutored edges off this young man laughingly, lovingly referred to as “Buffalo.”

In 1870 “Buffalo” left Meadville with a degree and an amazing wife, Susan Charlotte Barber, who was to act as amanuensis, researcher, carpenter, seamstress, unofficial preacher, penny-pincher, wife and mother. In their forty-one years of marriage, they shared ideas, scholarship, hardship, hard-won success. Once, when a disgruntled parishioner threatened to leave the church and take his dollars with him, Susan said, “Jenk, you preach what you believe, and if we have to, I can take in washing and you can saw wood.”

He edited Unity Magazine (1880-1918), a monthly compilation of liberal religious thought and influential social teachings that became so radically pacifistic towards the end of his life that it was temporarily suspended by the U.S. government.

In 1890, Jenkin and two others purchased Tower Hill near Spring Green and developed a Summer Pleasure Company where like-minded families could escape Chicago’s summer heat and wallow in the works of great authors and great preachers in one of Wisconsin’s most verdant valleys. (The valley that the family now calls “The Valley.”) Tower Hill was popular with summer-jaded Chicagoans and local farmer folk alike and added immensely to the intellectual climate of this most unusual valley where so many Lloyd Joneses held their homes.

During Chicago’s Columbia Exposition of 1893, Jenkin spearheaded the first World Parliament of Religions, bringing together religious leaders from the Near and Far East, Europe, Russia, India, Africa, and America in an effort to promote religious understanding, respect, and mutual tolerance. It was a coup without equal, as leaders of religions that had warred for centuries came together in Chicago and paused to look for common ground, common tolerance through seventeen breathtaking days of exploration, explanation, and egalitarianism. Thousands of eager listeners jammed the hall to hear these exotic, esoteric exponents of so many differing faces of God. For such a vast undertaking it was surprisingly rancor-free. The few Christian sects that broke the rules and proselytized were promptly squelched. This was a gathering of faiths—and each was to be given its due respect.

His fame reached wide, and brought to city folks’ attention the attractions of country schooling offered at high-minded Hillside Home School, run with exemplary care and professionalism by “the Aunts,” his sisters Jane and Ellen.

And he mentored his own extended family—brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews—who flourished as creative educators and hardworking husbanders of the soil. He was their window on a broader world, but their shared roots and ideals profoundly nourished his ministry.

Imagine our tiny Unity Chapel festooned with the flowers of the field and hosting world-respected religious leaders of varying faiths. They came to the Valley and spoke from the wooden pulpit in that tiny chapel because their friend, Jenkin, had asked them to.

The little Valley rang with happy tears when Brother Jenk spoke. His rich voice challenged the faithful to live their religion in the here and now. To do justice. To love mercy. To walk humbly with their God.

And he lived long enough to see those happy tears turn sad as he buried brother after brother, sister after sister, wife, nephew, friend.

To his pulpit at All Souls Church in Chicago Jenkin invited the progressive minds of the century. Brother preachers in differing faiths. Women. Blacks. Reformers. His pulpit and correspondence became a Who’s Who of liberal thought and far-flung social action. He supported unions, women’s suffrage, women ministers, humane societies, pacifism, minorities of all colors and faiths. A fellow minister referred to him as “our humanitarian cyclone.” As Jenkin himself once put it, “One must be where the stones fly.”

In 1884, “fly” the stones did. Jenkin was a stubborn man and, as secretary of the Western Unitarian Conference, he stubbornly refused any kind of credal doctrine that would limit the rights of an honest seeker of truth, whatever that seeker’s concept of God. The dispute became known as the “Issue of the West,” pitting Western Unitarian openness against Eastern Unitarian demands that Jesus be first and foremost “Savior.” The name “Unitarian” was dropped by Jenkin, and his became a church for “All Souls,” grounded upon Freedom, Fellowship, and Character in Religion.

Hearing in 1904 that the Lincoln birth cottage was in danger of purchase and exploitation by Wanamaker’s, one of the leading department stores of the east, he galvanized community leaders who had revered Lincoln—among them Mr. Collier of Colliers magazine, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), and Jenkin’s own son, Richard. Together they snatched the Lincoln farm from private purchase, saving it from ignominy and preserving it for the nation and posterity. He loved Lincoln, and wrote, preached, and lectured on the slain President with reverence and respect.

Once, during Jenkin’s last years, a little boy gaped at the elderly, wavy haired, white bearded gentleman with the merry blue eyes and genial smile. “Do you know who that is?” whispered his mother. “Oh yes!" gasped the awestruck boy. “It’s Santa Claus!”

And in a way, Jenkin was. His kindness was legendary. His gifts of intellect and moral challenge, profound. But he offered far more to the legions of souls with whom he came in contact.

In the end, the pacifism that had molded him as a young man alienated many when he was old. World War I loomed. Jenkin fought against the war through Unity Magazine, the pulpit, and on every podium he could find. He joined the Henry Ford Peace Ship in a vain effort to turn European belligerents away from conflict. It became a laughing stock. Longtime parishioners fell away in sadness, cut off from the man they had loved by his intensity in this cause. All his influence, all his lifetime achievements, seemed to evaporate in the face of hostility to his stand.

But when peritonitis hit and the grand old man lost his grasp on life, the tributes flowed. Page after page was written. It was national news. The bitterness of his last years was forgotten in the sum of all his accomplishments.

In the graveyard at Unity Chapel, a solemn, stark rectangle of polished gray granite rises from the ground. There are no frills, no soft edges. Only the flowers nodding at its base ease its uncompromising severity. On the plane facing the Chapel is carved:

One who never turned his back

But walked breast forward

Never doubted clouds would break

Never dreamed though right were worsted

Wrong would triumph

Held we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better,

Sleep to wake

The text was chosen by his second wife, Edith, but his descendants say they would have preferred another text for his marker, one much loved by Lincoln:

He sought to pull up a thistle and plant a flower wherever a flower would grow.

How difficult to try to sum up a life in a sentence.

Perhaps a reporter in the early 20th century who followed the Reverend Jenkin for a full day at All Souls Church—a day filled with meetings, preaching, writings, colloquies, counseling, humor, advice—best caught the essence of the man:

“The report of his sermon?

Why, HE is the sermon.”

—Georgia L. J. Snoke, great-granddaughter