Thomas

Thomas Lloyd Jones

1830 - 1894

Thomas was the eldest of the second generation of emigrant Joneses. He was thirteen years old when the family left Wales for Wisconsin. Like his next brother, John, he had already been a shepherd in the sheep pastures of Wales.

In Wisconsin, he began doing man’s work from the beginning, clearing the land and working the farm at Ixonia. By the time the family moved to the Spring Green area, Thomas was an aspiring builder and entrepreneur. With a neighbor, he set up a carpenter shop and lumberyard, planning to share in the growing prosperity of the area. An accidental fire wiped out the uninsured business. Thomas then became a builder as well as a farmer, but never attained the prosperity for which he worked so hard.

His mother Mallie’s second-sight was a gift that the whole family recognized. Once she awoke from a deep sleep to shake Richard and say, “Richard, Thomas is hurt!” Her dream showed Thomas with blood on his foot. Thomas didn’t come home that night and the next morning a neighbor pulled into the yard with an injured Thomas in his wagon—he had cut his foot with an axe.

Even in his childhood and youth the family regarded Thomas as frail. That is why it was a younger brother, Jenkin, who served in the Union Army during the Civil War.

A document written by Thomas’ son, Ed, indicates Thomas was the first family member to move across the river into what we call “The Valley.” He built his own farmhouse in 1861, and moved in with his new bride, Esther Margaretta Evans, from one of the more prosperous (and more cheerful) Welsh families in Spring Green.

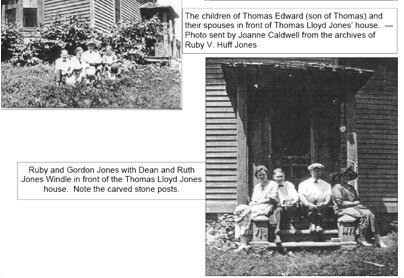

His son Ed described that first home as consisting of two rooms and a pantry downstairs and two sleeping quarters for the help, reached by an outside staircase, upstairs. Dimensions were about 24 x 16. A summer kitchen was later added, and Thomas’ family lived there until the now existing home was built for the family in 1878-1879. The cornerstone from that home is now in the possession of the Thomas family, pictured here at the home.

Once Thomas’ original home was built, he built his parents’ home, “Hillside Cottage,” and many other structures in the Valley.

After the Chicago Fire in 1871, he packed his tools and went to the city to get a share of the rebuilding work. Like many of his plans, this did not work out well, and he was soon home again.

Later, as a builder with some elementary architectural ability as well as carpentry skills, he built barns and homes in the neighborhood, the district school building where family members Jenkin Lloyd Jones and William Cary Wright preached in the years before Unity Chapel was built, and the second, larger, home for his family. A fall from a second-floor scaffold at his new home led to two broken ribs and a punctured lung. Increasing ill-health plagued him from that time forward.

Nevertheless, Thomas supervised the building of Unity Chapel, the original Hillside Home School, and the Assembly Hall at Tower Hill and, as his diaries show, assisted in specific manual labor.

Thomas and Esther had three children: Eve (or Evie) Jenk, a son who died before his third birthday; Thomas Edward (Ed); and Margaret Helen (Helen). They were a family steeped in literature and education. Esther was very well educated and Thomas loved to read aloud from the Bible, Shakespeare, and the American poets Longfellow and Whittier.

Perennially on the local school board, Thomas counted it one of the board’s most important achievements when his school district began to supply pupils with free textbooks. He also founded and managed a circulating library of current magazines for the local farmers.

As a farmer, Thomas was innovative and successful. The land he farmed was well cared for; he rotated his crops and prevented erosion. He was a pioneer in the growth of Wisconsin dairy farming, started the first cheese factory in the neighborhood, and invented an improved method for keeping milk cold. The farm, however, ceased to be a success after his debilitating fall from the scaffold. He was no longer able to take an active part in the farming and income dropped. A plan to recoup his losses by joining with James to buy some lumber-producing land made his financial situation worse instead of better.

All the family was of a religious nature, but Thomas was perhaps the most religiously inclined. His diaries show that he was a frequent churchgoer, often twice a day. It did not seem to matter to him what the denomination was; he went where he could be edified by sermons and prayer. His library included books on the Bible and theology.

Family tradition characterizes Thomas as a great lover of picnics. He was apparently the one most likely to suggest a picnic in “The Grove” and later the Chapel grounds. Thomas’ picnics ended with singing—much of it in Welsh—which he loved. He also shared his mother’s fondness for flowers. Among the few thing Mallie brought from Wales were Welsh seedlings, to bring a little bit of “home” to Wisconsin.

Thomas must have had a streak of vanity in him, too; his diary records more than a few trips to Dodgeville “to have a likeness taken.” He seems to have been the one Uncle to have a short, neatly trimmed beard.

In 1892, the year after Ed married Beulah Joiner, Esther died in a Chicago hospital of cancer. This was a devastating blow to Thomas. Her common-sense optimism had kept his natural gloominess in check. “The light of my life has gone out,” he wrote in his diary.

In the two years that remained of his life, he was cared for in the family home by Helen, and remained beloved by the children of Hillside Home School, who remembered him as their first manual training teacher. He died in l894 of an unrecorded illness of his respiratory system.

The farm and cheese factory had become so unprofitable by then that Ed and Helen sold their land to Hillside Home School and moved away from the Valley.

—Thomas Graham, great-grandson

Addendum from Georgia Snoke:

Little did Thomas know that one of his greatest gifts to his descendants would come from the laconic, sometimes indecipherable, notes he made in his daily diary. We can trace, for example, the building of Unity Chapel despite the way that life…and death…gets in its way:

Here is a sampling of Thomas’ involvement:

Thursday, May 13, 1886: Received a letter from Silsbee [the architect]

Friday, May 14: Church Dr [?] 1/2 day seeing to things and going to station looking for materials

Sat. May 16: Church Dr. 1 day for self going to station for goods and buying shingles in the afternoon.

Mon. May 17: Church Dr. Shingles and oil.

Wed. May 19: Self going for lumber and seeing to carpenters

Friday, May 21: Self went for and took [?] to fix tin gutter in church roof.

Saturday May 22: Self went to help fixing grave yard. Enos went to see Orren in Dodgeville.

Saturday, May 29, 1886: Church: getting brick.

Monday, May 31: Self went to church part of time. Tending mason.

Tuesday, June 22, 1886: Elvis [?] worked fixing post for church yard.

Friday, Aug. 6, 1886: Self finish painting. Commence on porch fixing floor. Wrote a letter to Aunt Jane D. Rees thanking for gift to the church of $1500.

Thursday, Aug. 12: Working at the church and started the privy. At noon the man came from Dodgeville with the news that Orren [his nephew, sister Margaret’s older son] was dead. Died about 9:00 AM this morning.

Monday, Aug. 9, 1886: Chris and self worked at church yard setting post and putting up [?]

Orren’s funeral in Dodgeville and the official Unity Chapel Dedication occurred the following weekend. But for Thomas’ diary, we would not have this intimate picture of the building of our chapel.

There are other amazing nuggets. Enos’ descendants were stunned to find that, amidst Enos’ healthy brood of children was one who didn’t make it. Until these four lines in Thomas’ diary were read, no one knew.

Oct. 18, 1888: Enos has a new baby boy.

Oct. 19, 1888: Baby not doing well.

Oct. 20, 1888: Baby very sick.

Oct. 22, 1888: Enos’ baby died today.

Picture the far side of the Chapel cemetery—right in front of Robert’s Meadow. On the same plane as baby Paul’s stone is a tiny marker in the corner. It says only “Baby.” For years it was assumed that it belonged to some unknown family in the Valley. And then the Thomas’ Diaries* surfaced. Is that the resting place of Enos’ infant? The cemetery was already being planned. Baby Paul, James’ toddler and the first to be interred there, already had his place. And infants of that era often were born—and died—nameless.

It is the day-to-day diarist who most often gives tomorrow’s historian the most intimate details. And so it was with Thomas. Denied an education himself, he educates us by sharing the daily demands of life at the end of the 19th century. This firstborn son of Richard and Mallie provided the stones and mortar, sweat and labor, for the physical foundation of the Lloyd Joneses of the Valley. While most of those buildings are long gone, the details he imparted to his diary paint us a picture of our ancestral family—their lives, deaths and needs—that enriches our knowledge today.

* The Thomas Diaries were gifted by Thomas Graham to the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison and may be read there today. (The Enos Diaries are in the possession of the Enos family. Another of our ancestors' diaries, we are told, were pitched out by a daughter-in-law in a fit of pique. An irreparable loss!)